Three things come together to make this post. The first is the paper The 2.5% Commitment by David Lewis, which argues essentially for top slicing a percentage off library budgets to pay for shared infrastructures.

Messaggi di Rogue Scholar

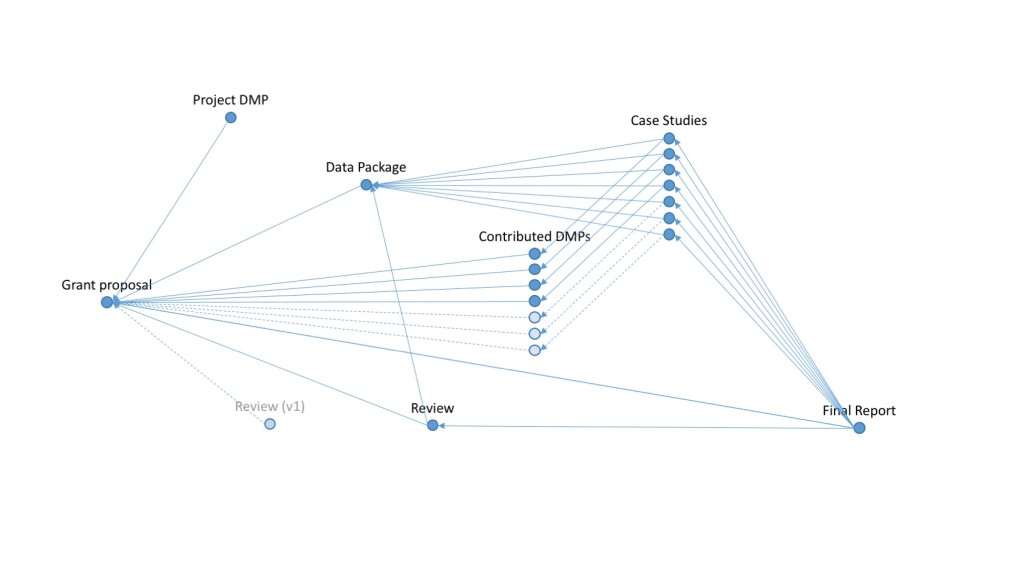

One of the things I wanted to do with the IDRC Data Sharing Pilot Project that we’ve just published was to try and demonstrate some best practice. This became more important as the project progressed and our focus on culture change developed. As I came to understand more deeply how much this process was one of showing by doing, for all parties, it became clear how crucial it was to make a best effort. This turns out to be pretty hard.

The following will come across as a rant. Which it is. But it’s a well intentioned rant. Please bear in mind that I care about good practice in data sharing, documentation, and preservation. I know there are many people working to support it, generally under-funded, often having to justify their existence to higher-ups who care more about the next Glam Mag article than whether there’s any evidence to support the findings.

There’s an article doing the rounds today about public understanding and rejection of experts and expertise. It was discussed in an article in the THES late last year (which ironically I haven’t read). I recommend reading the original article by Scharrer and co-workers, not least because the article itself is about how reading lay summaries can lead to a discounting of expertise.

A couple of ideas have been rumbling along in the background for me for a while. Reproducibility and what it actually means or should mean has been the issue du jour for a while.

The development of the acronym “FAIR” to describe open data was a stroke of genius. Standing for “Findable, Accessible, Interoperable and Reusable” it describes four attributes of datasets that are aspirations to achieve machine readability and re-use for an open data world.

Just to declare various conflicts of interest: I regard Gregg Gordon, CEO of SSRN as a friend and have always been impressed at what he has achieved at SSRN. From the perspective of what is best for the services SSRN can offer to researchers, selling to Elsevier was a smart opportunity and probably the best of the options available given the need for investment. My concerns are at the ecosystem level.

This is necessarily speculative and I can’t claim to have bottomed out all the potential issues with this framing. It therefore stands as one of the “thinking in progress” posts I promised earlier in the year. Nonetheless it does seem like an interesting framing to pursue an understanding of scholarly communications through. The idea of “the market” in scholarly communications has rubbed me up the wrong way for a long time.

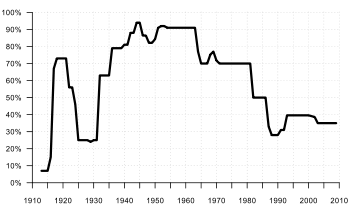

It has become rather fashionable in some circles to decry the complain about the lack of progress on Open Access. Particularly to decry the apparent failure of UK policies to move things forward. I’ve been guilty of frustration at various stages in the past and one thing I’ve always found useful is thinking back to where things were.

I think I committed to one of these every two weeks didn’t I? So already behind? Some of what I intended in this section already got covered in What are the assets of a journal? and the other piece Critiquing the Standard Analytics Paper so this is headed in a slightly different direction from originally planned. There are two things you frequently hear in criticism of scholarly publishers.