In the previous post, I outlined reasons why researchers don’t publish data, presented as evidence to the Royal Society’s Policy Study “Science as a Public Enterprise” Call for Evidence.

Messaggi di Rogue Scholar

Alistair Miles, of SKOS fame, who formerly worked in our research group, spent yesterday afternoon catching up with us, and has written a nice blog post on the MalariaGEN Informatics Blog describing our current activities, including our work on the Open Citations Corpus, and how they might intersect with the data management activities of the MalariaGEN, the Malaria Genome Epidemiology Network for which he now works.

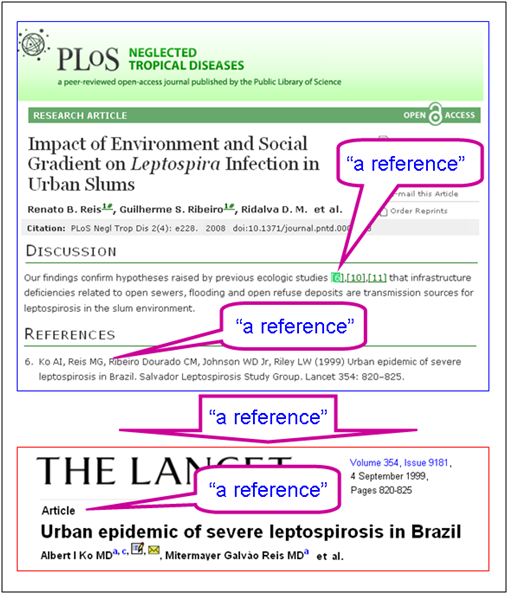

Reis et al . (2008) [1] cites an earlier paper from Albert Ko’s research group, Ko et al . (1999) [2]. In conventional parlance, as the following diagram shows, the word “reference” can mean either what is found in the text, what is found in the reference list, the act of citation, or the object of the citation itself, as in the sentence “All the references you will need to prepare for the journal club are on Kevin’s desk”.

As an approach towards developing best practice for data citation, I recently wrote a Data Citation Best Practice Discussion Document that is available on Google Docs, and that I have now slightly revised to Version 2 [1]. In that document, I first compared what is recommended by DataCite [2] and by Altman and King [3] with what currently practised by the Dryad Data Repository and what presently occurs ‘in the wild’ in a

DataCite is an international organisation, founded in 2009, which promotes the use of DOIs (Digital Object Identifiers) for published datasets, in order to establish easier access to research data, to increase acceptance of research data as legitimate contributions in the scholarly record, and to support data archiving to permit results to be verified and re-purposed for future study. Its founding members were the British Library;

The meaning of the word “dataset” is ambiguous, changing with context.

The DataCite Metadata Kernel version 2.0 [1] specifies the minimal metadata, and optional metadata, that should accompany a DataCite DOI for the identification of a published data entity. Within the Metadata Kernel document there is an XML mapping of these metadata terms, using DCMI Metadata Terms, and an example encoded in XML.

In addition to using CiTO and CiTO4Data to describe relationships of relevance to data entities, as discussed in the previous blog post, FaBiO, the FRBR aligned Bibliographic Ontology described elsewhere, another member of the suite of SPAR (Semantic Publishing and Referencing) Ontologies, also has a number of classes and properties specifically designed for addressing data, software, metadata and other non-bibliographic entities.

This is the first of a series of blog posts on the Open Citations blog that address the problem of citing data entities, for example a data package in a data repository, rather than bibliographic entities such as journal articles. For these purposes, the existence of DataCite to assign DOIs to datasets, and extensions to the SPAR (Semantic Publishing and Referencing) Ontologies to handle data items, are both important.

In the previous blog post, I made a textual comparison between BIBO v1.3, the Bibliographic Ontology developed by Bruce D’Arcus and Frédérick Giasson, and FaBiO, the FRBR-aligned Bibliographic Ontology.