In the mid-2010s, many Nordic public service broadcasters seemed to more or less give up on trying to reach the teenage audiences.

In the mid-2010s, many Nordic public service broadcasters seemed to more or less give up on trying to reach the teenage audiences.

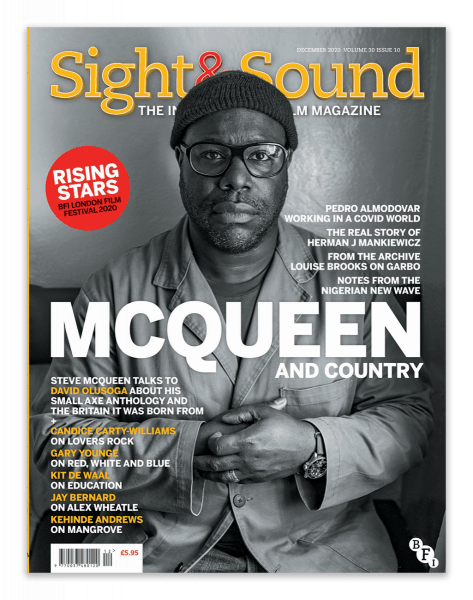

by Ian Greaves One of the many peculiarities of life in lockdown has been to witness the turmoil it has created for Sight and Sound , a magazine used to reporting from festivals and film sets around the globe. Like the rest of us, they have had to adapt to a different way of living. To their sometimes evident horror, this now includes television. Fig. 1: BFI’s Sight &

Oh blimey is it that time again already? I mean it seems like only a few weeks since it was time for me to get on with getting things off my chest through this fine organ (can we call it an organ if it’s online?) but here we are again and, hope you’re all ready for my latest incoherent ramblings about the state of the nation, the world, and the box of lights in the corner that never has anything on it anymore. Really. We are bored.

Many years ago, whilst preparing to teach British Cinema History at LJMU, under the brilliant, but now sadly departed Nickianne Moody, i was tasked to research the history of British Music Hall. The main thrust of the module was to show how British cinema was the product, not of the theatre, but of the music hall tradition and working-class popular culture.

The popular and critical success of contemporary UK drama series including Sex Education (Netflix, 2019 -), Normal People (BBC Three/RTE One/Hulu, 2020) and I May Destroy You (BBC/HBO, 2020), all of which have been praised for their complex depictions of sexual intimacy and consent, has drawn increasing attention towards the relatively new role of the intimacy coordinator in television production.

<Graeme Garden 1968>DO YOU KNOW what the words starting with ‘D’ and ‘W’ written on this partially obscured file are? Fig. 1: DO YOU KNOW what the words starting with ‘D’ and ‘W’ written on this partially obscured file are? Yes – that’s right! Fig 2: Yes – that’s right.

The topic of this blog, which concerns mediations of a particular species of dinosaur across factual television, museum and visitor reception contexts, might seem a little distant from current debates that are taking place within television studies.

There used to be a time when the only place to learn how to write for Danish film and television was the National Film School of Denmark (NFSD) that currently accepts six screenwriters for the 4-year programme every second year.

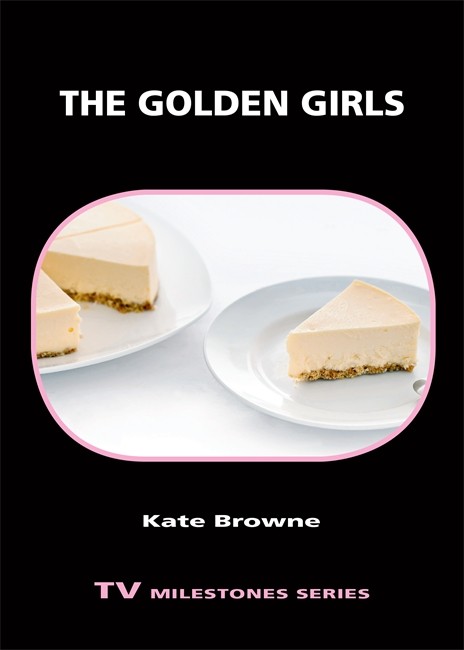

A few months ago, I was holding a book that I was going to review. I noted with a start the sheer pleasure of handling it. Everything – from the cover to the evocative illustrations to the quality of the paper to the clear typeface – was aimed at making this book an aesthetically pleasing experience.

In his book Seeing Things (2000), John Ellis hailed the emergent multi-platform environment of the twenty-first century as the ‘era of plenty’. When I ask my students to define what is meant by ‘plenty’, they invariably reply ‘a lot’. Well, yes – but that lacks one vital nuance. Plenty, I explain to them, means more than we need. Quite possibly, a lot more.