Stereoselectivities of Proline-Catalyzed Asymmetric Intermolecular Aldol Reactions.

Astronomers who discover an asteroid get to name it, mathematicians have theorems named after them. Synthetic chemists get to name molecules (Hector's base and Meldrum's acid spring to mind) and reactions between them. What do computational chemists get to name? Transition states! One of the most famous of recent years is the Houk-List.

In the last 12 years or so, the area of enantioselective organocatalysis has blossomed, and an important example involves the asymmetric amino acid (S)-proline (below, shown in green). As its enamine derivative (below, shown in blue), it can catalyse the aldol condensation with an aldehyde or ketone to form two new adjacent stereogenic centres resulting from C-C bond formation (shown below as (R) and (S) as attached to the carbons connected to the red bond).

The Houk-List transition state was located for this reaction, and as a useful model for rationalising the stereospecificity of this reaction it has become justly famous (although to be fair, other models have also been proposed). The challenge is to identify the factors selecting for just one stereoisomer (S,R in this case) over the other three (a similar challenge is described in this post for the heterotactic polymerisation of lactide). Houk, List and co-workers constructed their model (the example shown below is for R=isopropyl) as follows.

They employed a B3LYP/6-31G(d) density functional model.

The geometry of the transition state was located for all four diastereomeric transition states using this method. Importantly, this geometry was for the gas phase, which provided a value for ΔG298†.

These free energies were then corrected for the (relative) solvation energies of the four transition states. This was essential, since in the mechanism shown above, a neutral reactant gives a zwitterionic product, via a partially ionic transition state (indeed, the dipole moment of these transition states is around 10D).

The resultant Houk-List model then predicted that of the four isomeric transition states, the lowest was (as shown above) the (S,R) diastereomer.

This particular transition state geometry has an interesting feature involving a 9-membered ring, large enough to accommodate a linear proton transfer without strain, by virtue of a* trans* double bond motif (the C=N bond). The (S,S) and (R,S) isomers have a cis motif instead at this location.

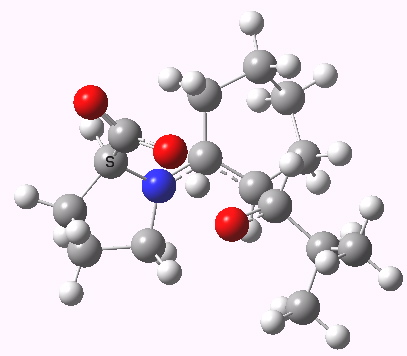

Houk-List transition state. Original

geometry.

Houk-List transition state. Original

geometry.

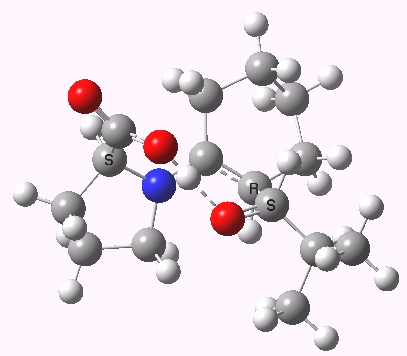

Well, this transition state is now nine years old. Unlike asteroids, or mathematical theorems, or indeed molecules and their reactions, a transition state is a slightly more ephemeral object. Its features and properties do rather depend on the particular quantum model used to construct it. There is one feature of the model, necessary in 2003, but no longer so in 2012. This was the use of a gas-phase optimised geometry, augmented at that geometry with a so-called single-point solvation energy correction. Nowadays, the solvation correction is included in the energy used in the geometry optimisation, which now properly reflects the effect of the solvation. Re-optimisation with this inclusion, at the ωB97XD/6-311G(d,p)/SCRF=dmso level thus updates the original Houk-List geometry.

(S,R) Houk-List transition state, updated geometry. Click for 3D

- The most significant changes involve the O…H—O bond lengths. Respectively 1.13/1.31Å in the original, they change to 1.06/1.40Å at the new level.

- The forming C-C bond changes in length from 1.89 to 2.05Å (the latter, it has to be said, being a much more "normal" value for a transition state).

- Whilst these might not seem very great changes, we do not yet know how they might impact upon the relative free energies of the four transition states. Houk and List reported the (S,R), (R,R), (S,S) and (R,S) relative free energies as 0.0, 6.7, 7.8 and 4.6 kcal/mol. The updated values for (S,R), (R,R), (S,S) and (R,S) [click on preceding links to view models] are 0.0, 6.0, 5.7 and 5.4 kcal/mol [click on preceding links to view calculation archives], which represent only minor changes to these energies.

- The (S,S) diastereoisomer is an interesting outlier. The transition state normal mode wave numbers are -373, -481, -815 and -402 cm-1 respectively and the O…H…O bond lengths for (S,S) are 1.18 and 1.20Å, a rather more symmetrical proton transfer than the other three.

Which brings us to the main point; what is the origin of the diastereoselectivity? An NBO analysis can compare the total steric exchange energy (due to Pauli bond-bond repulsions) of the four isomers, which turns out to be respectively 1214, 1221, 1235 and 1229 kcal/mol. In other words, the favoured isomer has the smallest steric exchange energy. Of course this one term is not the only contributing factor, and a more elaborate analysis will no doubt provide further insight.

So an update to the Houk-List transition state reveals the general characteristics are intact and it is still a very useful model for analysing stereoselectivity in proline organocatalysis.

Postscript: The Intrinsic reaction coordinate (for (S,S) ) is shown below.

Additional details

Description

Astronomers who discover an asteroid get to name it, mathematicians have theorems named after them. Synthetic chemists get to name molecules (Hector's base and Meldrum's acid spring to mind) and reactions between them. What do computational chemists get to name? Transition states! One of the most famous of recent years is the Houk-List.

Identifiers

- UUID

- 934bcd62-b31b-4207-86b7-b2fe2e07b4e3

- GUID

- http://www.ch.imperial.ac.uk/rzepa/blog/?p=6477

- URL

- https://www.ch.imperial.ac.uk/rzepa/blog/?p=6477

Dates

- Issued

-

2012-04-22T12:49:54

- Updated

-

2013-10-12T10:22:17