The DFG is a very progressive and modern funding agency. More than two years ago, the main German science funding agency signed the “Declaration on Research Assessment” DORA.

Messaggi di Rogue Scholar

So this happened: Zootaxa is a hugely important journal in animal taxonomy: On one hand one could argue that impact factor is a bad way to measure academic impact, so it's tempting to say this simply reflects a poor metric that is controlled by a commercial company using data that is not open.

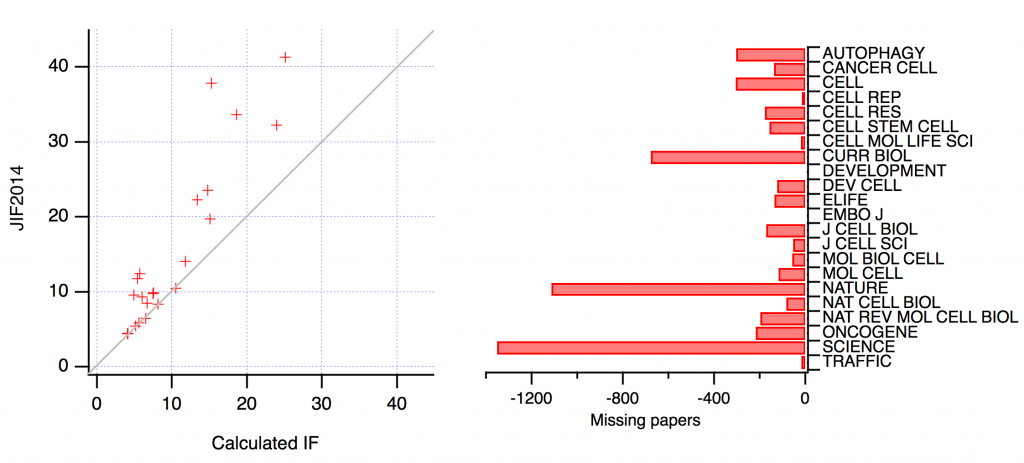

There is an entertaining rumour going around about the journal Nature Communications . When I heard it for the fourth or fifth time, I decided to check out whether there is any truth in it. Sometimes it is put another way: cell biology papers drag down the impact factor of Nature Communications , or that they don’t deserve the high JIF tag of the journal because they are cited at lower rates. Could this be true?

**Shallow Impact. Tis the season. **In case people didn’t know— the world of scientific publishing has seasons: There is the Inundation season, which starts in November as authors rush to submit their papers before the end of year. Then there is the Recovery season beginning in January as editors come back from holidays to tackle the glut.

I have written previously about Journal Impact Factors (here and here). The response to these articles has been great and earlier this year I was asked to write something about JIFs and citation distributions for one of my favourite journals. I agreed and set to work. Things started off so well. A title came straight to mind.

I was interested in the analysis by Frontiers on the lack of a correlation between the rejection rate of a journal and the “impact” (as measured by the JIF). There’s a nice follow here at Science Open.

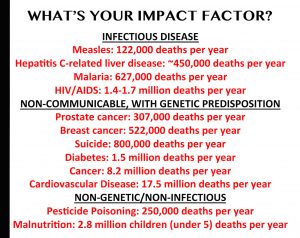

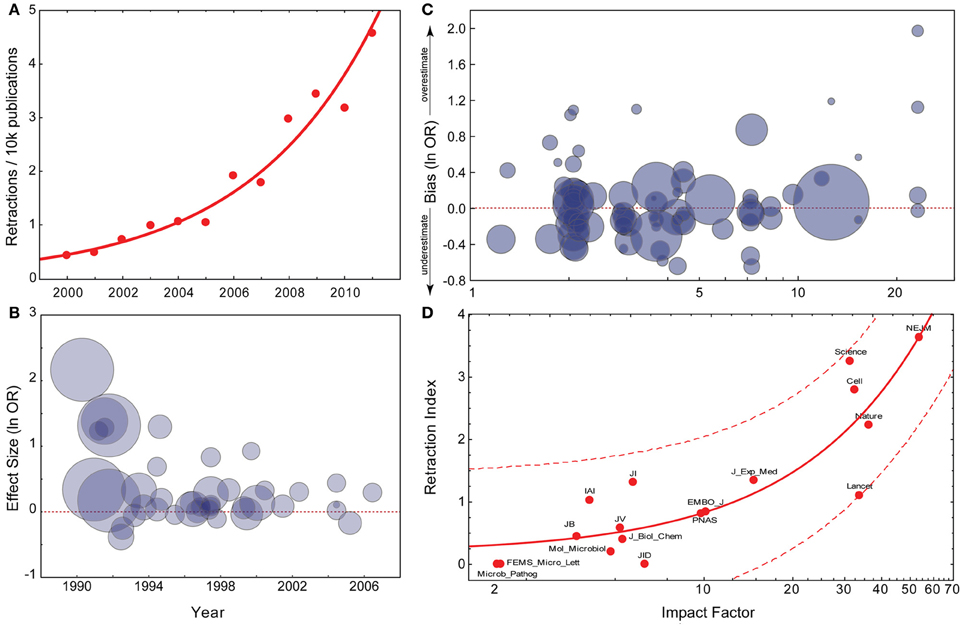

tl;dr: Data from thousands of non-retracted articles indicate that experiments published in higher-ranking journals are less reliable than those reported in ‘lesser’ journals. Vox health reporter Julia Belluz has recently covered the reliability of peer-review.

Over the last decade or two, there have been multiple accounts of how publishers have negotiated the impact factors of their journals with the “Institute for Scientific Information” (ISI), both before it was bought by Thomson Reuters and after. This is commonly done by negotiating the articles in the denominator.

There have been calls for journals to publish the distribution of citations to the papers they publish (1 2 3). The idea is to turn the focus away from just one number – the Journal Impact Factor (JIF) – and to look at all the data. Some journals have responded by publishing the data that underlie the JIF (EMBO J, Peer J, Royal Soc, Nature Chem). It would be great if more journals did this.

In the last “Science Weekly” podcast from the Guardian, the topic was retractions. At about 20:29 into the episode, Hannah Devlin asked, whether the reason ‘top’ journals retract more articles may be because of increased scrutiny there. The underlying assumption is very reasonable, as many more eyes see each paper in such journals and the motivation to shoot down such high-profile papers might also be higher.