A recent OASPA guest post reminded me of something I have been wondering about for several years now. What sinister time travel device is keeping some sections of the scholarly ecosystem from leaving the past and coming back to the present?

Messaggi di Rogue Scholar

Most academics would agree that the way scholarship is done today, in the broadest, most general terms, is in dire need of modernization. Problems abound from counter-productive incentives, inefficiencies, lack of reproducibility, to an overemphasis on competition at the expense of cooperation, or a technically antiquated digital infrastructure that charges to much and provides only few useful functionalities.

The academic journal publishing system sure feels all too often a bit like a sinking boat: we have a reproducibility leak an affordability leak a functionality leak a data leak a code leak an interoperability leak a discoverability leak a peer-review leak a long-term preservation leak a link rot leak an evaluation/assessment leak a data visualization leak … … … and even a tiny access leak still remains even after 30 years of trying to fix it.

For a few years now I have been arguing that in order to accomplish change in scholarly infrastructure, it likely is an inefficient plan by funding agencies to mandate the least powerful players in the game, authors (i.e., their grant recipients). The legacy publishing system still exists because institutions pay for its components, publishers.

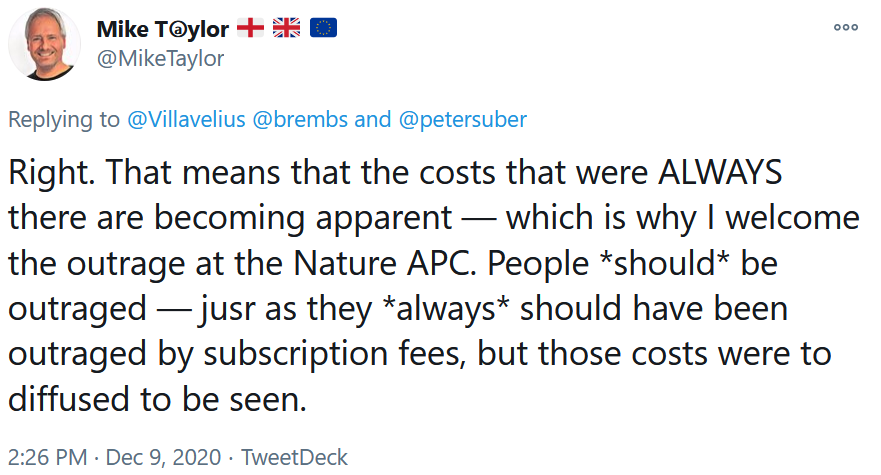

There has been some outrage at the announcement that Nature is following through with their 2004 declaration of charging ~10k ($/€) in article processing charges (APCs). However, not only have these charges been 16 years in the making but the original declaration was made not on some obscure blog, but at a UK parliamentary inquiry. So nobody could rightfully claim that we couldn’t have seen this development coming from miles away.

Last week, there was a lot of outrage at the announcement of Nature’s new pricing options for their open access articles. People took to twitter to voice their, ahem, concern. Some examples: There are many more that all express their outrage at the gall of Nature to charge their authors these sums,. even Forbes interviewed some of them.

Just before Christmas 2019, the Washington Post reported, based on “people familiar with the matter”, that the US Justice Department were investigating the Sci-Hub founder Alexandra Elbakyan for potentially “working with Russian intelligence to steal U.S. military secrets from defense contractors”. Besides such a highly unusual connection, the article also reiterated unsubstantiated (but mainly circulated by publishers) allegations that access

Think, check, submit: who hasn’t heard of this mantra to help researchers navigate the jungle of commercial publishers? Who isn’t under obligation to publish in certain venues, be it because employers ask for a particular set of journals for hiring, tenure or promotion, or because of funders’ open access mandates?

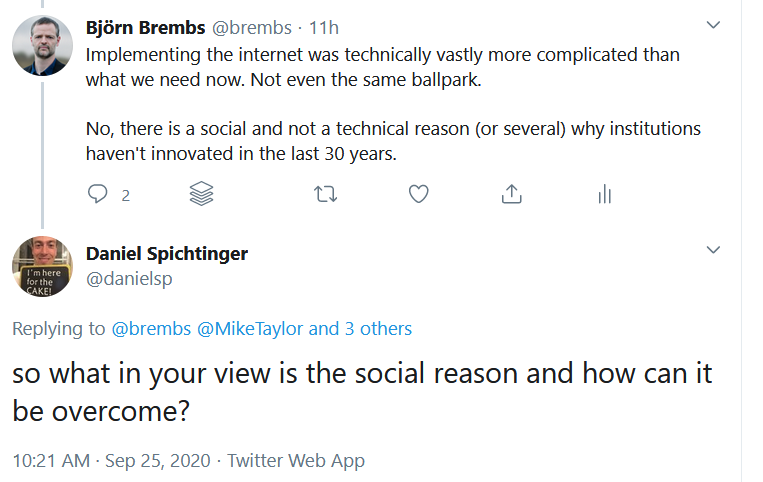

Until the late 1980s or early 1990s, academic institutions such as universities and research institutes were at the forefront of developing and implementing digital technology. After email they developed Gopher, TCP/IP, http, the NCSA Mosaic browser and experimented with Mbone. Since then, at most academic institutions, infrastructure has moved past the support of email and browsers only at a glacial pace.

There are regular discussions among academics as to who should be the prime mover in infrastructure reform. Some point to the publishers to finally change their business model. Others claim that researchers need to vote with their feet and change how they publish. Again others find that libraries should just stop subscribing to journals and use the saved money for a modern publishing system.