The withdrawal of the US from UNESCO: What does this mean for Open Science?

Creators & Contributors

A shorter version of this blog post in Dutch has been published earlier on the website of Nederlandse UNESCO Commissie.

On July 22, 2025, the US Department of State under the Trump administration issued a statement announcing the country's withdrawal from the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). The withdrawal will take effect on December 31, 2026, in line with Article II(6) of the UNESCO Constitution. The wording of the statement outlines the US disagreement with UNESCO in no uncertain terms:

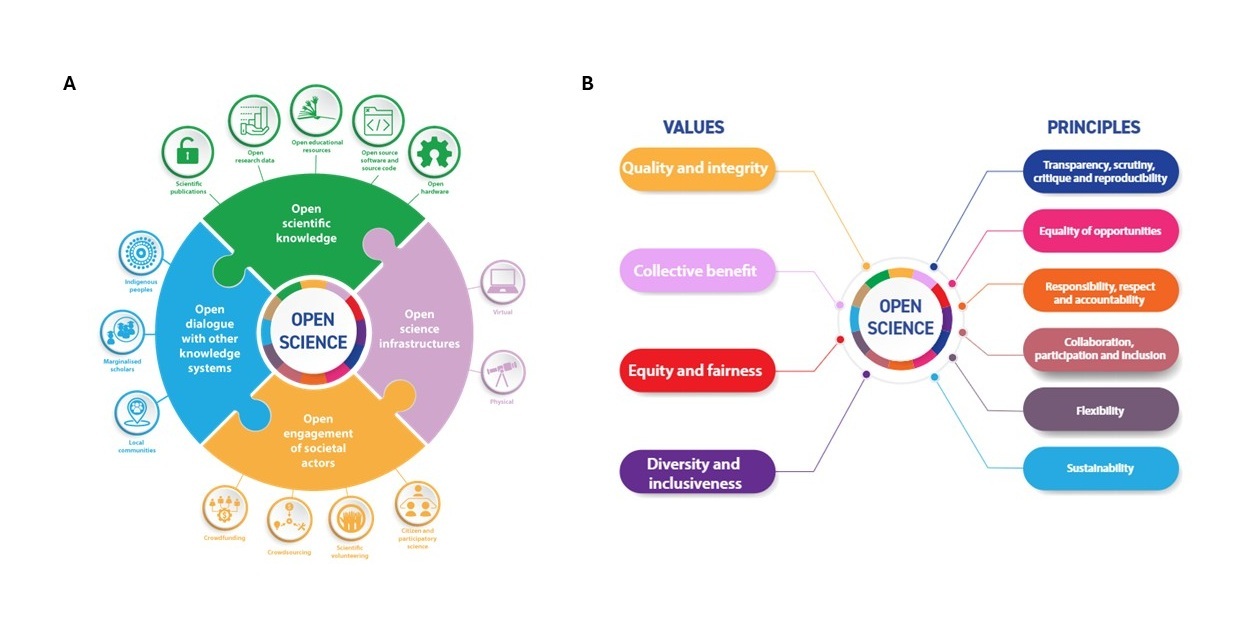

The withdrawal from UNESCO leaves many questions unanswered regarding the continuation of activities and endorsements made by the US as a member state. In relation to Open Science, it becomes vital to ask what the implications are for the UNESCO Recommendation on Open Science adopted in 2021 by all member states including the US (Figure 1A).

Prior to the 2025 withdrawal, the US has been a strong supporter of Open Science and evolving Open Science infrastructures through publicly-funded activities, community-led initiatives and commercial services. Indeed, in 2023, NASA declared the Year of Open Science and launched an ambitious effort to develop Open Science training and capacity-building that involved contributions from scholars around the globe.

While the Open Science community in the US undoubtedly remains committed to advancing open research practices, the Trump administration has already demonstrated a commitment to policies that directly stand in conflict with the values of Open Science illustrated in Figure 1B. In relation to equity and inclusiveness, the dismantling of federal Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) programs has led to job losses and programme closures. For quality and integrity, the removal of datasets and other research outputs from the academic record is cause for concern. Similarly, the sudden defunding of research infrastructures will have significant long-term implications. For collective benefit and fairness, the withdrawal of funding from research programmes and the alteration of curricula or the request for changes raise concerns. Moreover, the policies of the Trump administration have led to travel disruptions and bans, the loss of collaboration funding and other negative effects for the US engagement with global research.

Implications for Open Science Infrastructures

The prevalence of Open Science infrastructures in the US, and the rapidly changing political landscape have significant implications for Open Science. Recent studies have highlighted the concentration of essential Open Science infrastructures within the US. Bezuidenhout and Havemann (2020) and Invest in Open Infrastructure (2024) detail the unequal distribution of infrastructures across the world. Beigel (2024) further outlines the US-heavy distribution of repositories across the world. A growing number of concerns are being raised about the national management of globally important research infrastructures, including key databases, preprint servers (such as arXiv and bioRxiv), software versioning platforms (such as GitHub) and academic networking sites. As highlighted by Goodman (2025), "we must stop relying on scientific infrastructure provided by one nation or organisation. Any single point of failure makes science fragile".

Further studies have highlighted the variability with which these sanctions are applied within affected organisations, suggesting that there is little consistency when it comes to applying restrictions. All of these studies suggest a chaotic network of geoblocking and restrictions underpinning the Open Science landscape. The impact of sanctions, of course, has broader impact on Open Science beyond access to open resources. In addition to the increasingly-reported travel restrictions, these sanctions affect online financial transactions for individuals in these countries. This means that they are often unable to pay APCs, conference fees, membership fees, or resource costs if the receiver is based in the US.

The structure of this problem is thus as follows:

- A large number of critical research infrastructures and providers (federally-funded ones, but also the charitable and non-profit organisations) are located in the US.

- Any US organisation - whether non-profit, federally funded, or proprietary - must comply with (financial) sanctions imposed by the Trump administration against certain countries.

- Sanctioned countries cannot purchase services or goods from US organisations. This means that individuals in these countries are unable to use the services provided by these infrastructures. This can include access to websites, membership of organisations, purchase of goods.

Digital Object Identifiers as an Example

To illustrate this problem we can use the example of Digital Object Identifiers (DOIs). One of the fundamental drivers of the Open Science movement has been the efforts behind making the digital record (articles, datasets and software) findable and persistent in the long term. This is enabled by Persistent Identifiers (PIDs) such as DOIs: unique, permanent codes that always point to the same digital object. Even if an article or dataset moves to another website, the DOI still works and leads you to the right place.

DOIs have become a ubiquitous part of the Open Science landscape and provide a vital means of ensuring the long-term persistence of digital records. DOIs have transformed the research landscape, enabling objects to be persistently identified by humans as well as machines. DOIs are "minted" by a small number of organisations, of which DataCite and Crossref are perhaps the most prominent.

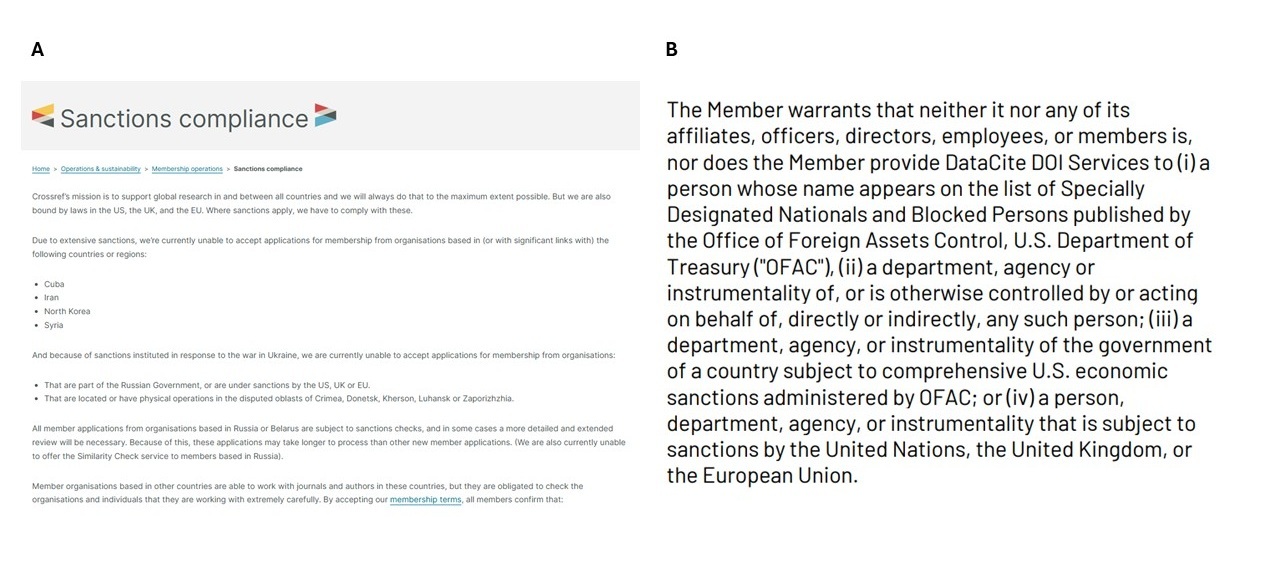

CrossRef is a non-profit organisation located in the US made up of member organisations that use their DOIs to manage digital outputs. Nonetheless, as it is bound by US, UK and EU sanctions, it does not accept membership applications from organisations in sanctioned countries, or those with significant links to those countries. This directly limits access to content from those regions, as publishers are not able to register DOIs for their publications. In their sanctions compliance statement (Figure 2b), Crossref identifies four countries in particular with which it is prohibited to transact: Cuba, Iran, North Korea and Syria. While slightly less explicit, DataCite's terms and conditions (Figure 2b) set out similar restrictions against countries under US economic sanctions.

Let us consider the inclusion of Cuba on the lists in Figure 2. While the US has a long-standing trade embargo against Cuba which includes restrictions on trade and financial transactions, neither the EU nor the UK hold financial sanctions against Cuba. Thus, Cuba is excluded solely on the basis of US foreign policy. The ability for a single country to determine who can engage with critical services such as DOI providers has profound implications for the UNESCO Recommendation on Open Science. Should a single country - and a non-UNESCO member at that - be able to determine which other signatories can benefit from, and engage in, a global movement?

Taken together, the evidence is disturbing. If Open Science infrastructures continue to be concentrated in the US it is likely that the Trump administration's foreign policy will determine who is able to be involved in global open research. Of course, it is possible to question the timing of these concerns. For example, Cuba has been sanctioned by previous US administrations. Nonetheless, when the US ceases to be a UNESCO member state, opportunities for dialogue and discussion about balancing national security against foreign interest shrink considerably.

The persistent influence of the Trump administration on the Open Science movement therefore has direct implications for key UNESCO Open Science ambitions. This relates not only to open scientific knowledge, but also the engagement of marginalised scholars, other knowledge communities and societal actors. Indeed, it is difficult to see how the values of Open Science can be transparently maintained if such insidious and malign geopolitical forces operate as an undercurrent to the global movement towards openness.

Where do we go from here?

Recognising that the global vision for Open Science is vulnerable to geopolitics highlights the urgency of initiating discussions about the location, ownership and sustainability of the key infrastructures that support open scholarship. How can we ensure that the values of quality/integrity, collective benefit, equity/justice and diversity/inclusiveness are supported - and not undermined - by the infrastructures underpinning Open Science?

Discussions around ownership of open research infrastructures are not new. For example, the open workflow platform Research Equals includes a "poison pill" agreement that makes it difficult to be sold. Other options of increasing community control with "exit to community" models are already being considered. Nonetheless, what is urgently needed is critical thinking about how new multi-country organisations can be established that are community-run and resilient to geopolitical influences. Knowledge Commons, for example, proposes to "establish three linked but independent non-profit public-benefit companies incorporated in the US, Europe and South Africa, all dedicated to the social and technological processes of gathering, preserving and ensuring the public accessibility of academic research". It hopes that this network can ensure that research can be protected from censorship, interference and digital ephemerality.

Already there are many calls for developing resilience within global research. The International Science Council's report "Protecting Science in Times of Crisis" outlines multi-level and multi-phase approaches to resilience. Nonetheless, resilience strategies and actions force an uncomfortable question for the Open Science community. Should a country whose national and foreign policies stand at odds to the UNESCO Open Science values, and who is no longer a signatory to a global Recommendation on Open Science, have the power to decide who and what gets to be involved? If not, how do we safeguard the UNESCO Recommendation on Open Science against the growing storm?

Header image by Nick Fewings on Unsplash.

DOI: 10.59350/wt0hr-w6728 (export/download/cite this blog post)

Note (14-11-2025): To improve clarity, 'but also the non-profit organisations known as 501c3 organisations' has been changed to 'charitable and non-profit organisations' and 'CrossRef is a 501c3 company' to 'CrossRef is a non-profit organisation'.

Additional details

Description

A shorter version of this blog post in Dutch has been published earlier on the website of Nederlandse UNESCO Commissie.

Identifiers

- UUID

- ef341f32-1c1b-4f27-b623-81676f375809

- GUID

- https://www.leidenmadtrics.nl/articles/the-withdrawal-of-the-us-from-unesco-what-does-this-mean-for-open-science

- URL

- https://www.leidenmadtrics.nl/articles/the-withdrawal-of-the-us-from-unesco-what-does-this-mean-for-open-science

Dates

- Issued

-

2025-11-05T13:58:00

- Updated

-

2025-12-01T07:29:40